Rosedale (and more) Remembered

|

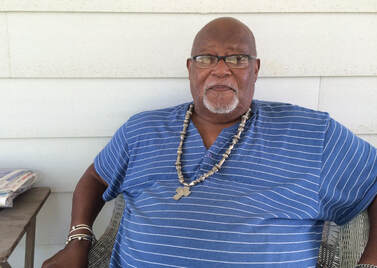

Cool breezes blow across the expansive porch where James Starling sits contently on a cushioned chair and watches cars go by. A retired educator after 35 years and multiple college degrees, Starling appears to be in his 60s, his rich brown skin hiding another decade. When a car horn sounds from Rt. 113, the well-known Milford, DE Councilman – now in his 9th term – acknowledges the driver with a wave. Afterward Starling sits at the kitchen table and, with his cane, taps an unconscious rhythm that punctuates certain memories about family and community. He’s been asked to talk about the former Rosedale Beach and Hotel Resort for the local Mispillion Art League, and it becomes part of a deeper conversation about Delaware and race.

|

"Back then, Blacks had nowhere else to go"

Starling’s tales about the Millsboro, DE facility are prefaced by the important fact that “back then, Blacks had nowhere else to go." He continues, "There was Riverdale that belonged to the (Nanticoke) Indians, then Oak Orchard and that was for the whites. So the Blacks went down to the Rosedale Beach. There was everything there for us. Mr. and Mrs. Burton (the owners) had a campsite, a big hotel, and there were 15-20 cottages back there. Later on they had a ball diamond and we played there on Sunday.”

Living in Lincoln, DE with his mother and grandparents, Starling was irritated that he couldn’t go to high school in nearby Milford because of his skin color. “We took the bus to Jason High School (in Georgetown). I had to walk about a mile and half to the bus in all kinds of weather; we caught the bus and rode forever. I could see Milford High School, but couldn’t go there. Jason was the only Black high school in Sussex County. And before it opened, Blacks had to go up to Dover (more than 20 miles away) for Grades 10, 11, and 12. There was no bus; you had to live on campus and very few people could afford that.”

|

Starling and his friends also hid in the woods in Lincoln to watch meetings “at the corner on the highway by a tractor place” led by white supremacist Bryant Bowles. A bitter opponent of racial integration in Delaware, Bowles formed the National Association for the Advancement of White People (NAAWP) and gained national attention for his pro-segregation boycott of Milford High School. (Some believe that cross burning and other activities caused desegregation to be delayed for another decade in some parts of Delaware). Starling quietly summarizes: “We had to bear it and we had to go through it.”

(Bowles was eventually indicted by a Dover criminal court for making racially threatening statements at a rally, but the jury found him not guilty, possibly influenced by a juror who was a member of the NAAWP. Delaware later revoked NAAWP’s corporate charter, but it was revived by a former KKK member in New Orleans for a new white supremacist organization that is active today). |

Photos: Library of Congress, Prints & Photos,

[LC-USZ62-126462 and LC-USZ62-138224] |

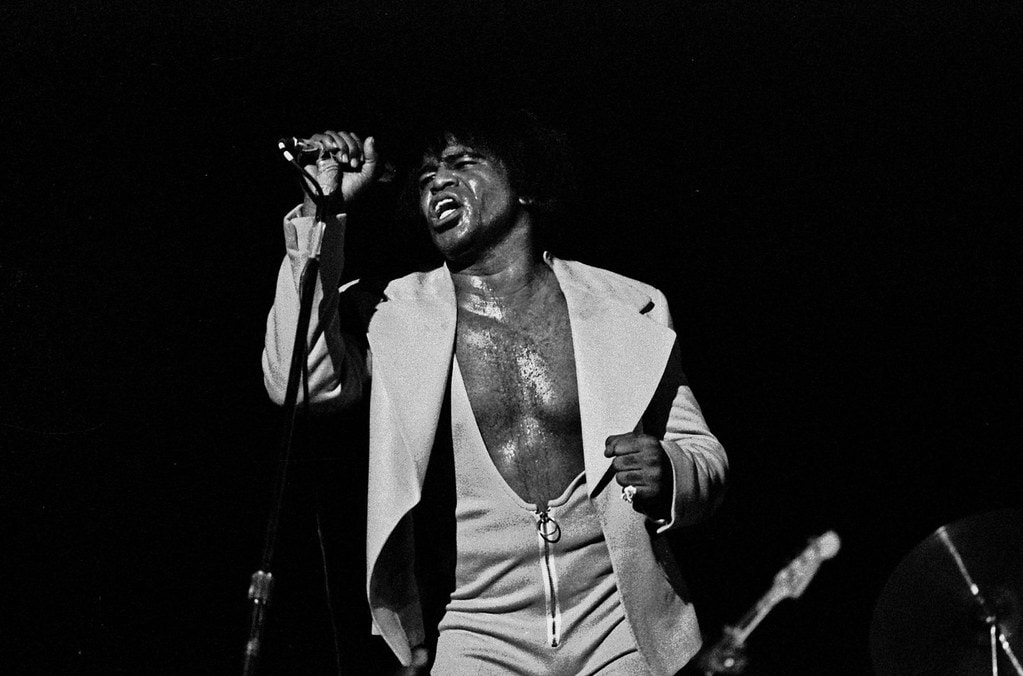

Starling graduated from college in 1961, after attending Delaware State College (now University), the only college that admitted Blacks. His college roommate had a boat, and when the Rosedale acts were outside, “we would take my friend’s boat and park close to the beach. I saw the Drifters, James Brown, and Little Richard. They would stay Saturday nights at the hotel and perform on Sunday afternoons. When it was James Brown, the place was loaded. You could sit out and have drinks, and if you wanted to go back in, you could take a dance.”

In 1962, a severe storm destroyed the Rosedale boardwalk and it was not replaced. As Delaware’s beaches, hotels and performance venues were integrated, Rosedale’s popularity among Blacks began to decline. One day, as Starling was teaching 4th and 5th grade a few miles away, Rosedale co-owner Mr. Burton died. (By then Starling was also married and a father of two). “Mrs. Burton came out to the school to see me and wanted to sell all of it for $90,000. I had just been teaching three or four years, and I had nothing.” Mrs. Burton felt she could not operate the facilities on her own. Starling and others knew the property was valuable, but when they attempted to form a Black organization to purchase the resort, sufficient funds could not be raised.

As the Rosedale property sat empty, Starling and his wife moved to Milford in 1973. Starling “loves it here” and has never moved away, but he remembers the racial hatred that permeated even local entertainment. “The big Jesus Love Temple used to be a movie theater called the Schine, and there was a smaller one around the corner called the Shore. We couldn’t sit in the bottom of either one – we had to sit up top (in the balcony). They had ushers who stood right there at the door and you knew automatically…just go upstairs. You didn’t ask questions.”

As the Rosedale property sat empty, Starling and his wife moved to Milford in 1973. Starling “loves it here” and has never moved away, but he remembers the racial hatred that permeated even local entertainment. “The big Jesus Love Temple used to be a movie theater called the Schine, and there was a smaller one around the corner called the Shore. We couldn’t sit in the bottom of either one – we had to sit up top (in the balcony). They had ushers who stood right there at the door and you knew automatically…just go upstairs. You didn’t ask questions.”

Starling’s wife, Dr. Jeanel Daniels-Starling, eventually taught school in Milford and by 1985, became its first African American assistant principal (and Sussex County’s first Black woman principal). In 1995, she was voted Delaware’s Elementary Principal of the Year. Like Starling’s grandfather who raised him, she also preaches for the United Methodist Church.

Starling pauses and taps his cane on the kitchen floor twice. “You know, it was one of the top spots in Delaware, especially lower Delaware. Nat King Cole and the big Black acts mainly came down to Rosedale Beach, not Wilmington or Dover. Everything went on there. The water was beautiful. They had all the recreational activities - fishing, boating, baseball games, open beach. They had it all and it was prosperous.”

© 2016 Joanne Caputo